Quantum Theory

Particle or Wave

In our familar world, the way things move and interact are completely descibed by so-called classical physics. At the sub-atomic scale classical physics simply doesn’t work. We are unable to describe how things work. We can only devise experiments and observe what happens.

Unless there is a fundamental breakthrough in our understanding, the only source of truth is making observations and formulating rules to describe them.

Two Slit Experiments

The two split experiments showed part of the bizarre nature of sub-atomic particles.

Two Slit Bullets

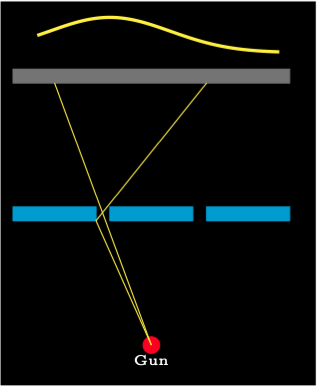

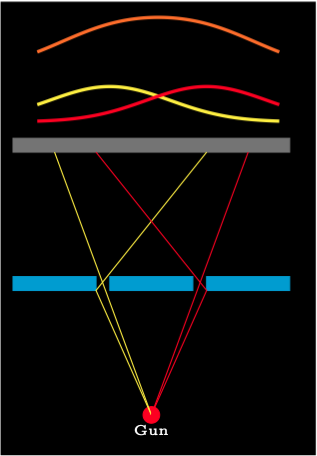

In this experiment consider a rather out of control gun that sprays bullets in random directions over a small angle. The gun is aimed at a bullet proof wall that has two slits that are large enough for a bullet to pass through. The bullets can’t break up and either pass through a slit intact or don’t pass through a slit. Behind the slits is a wall that captures every bullet that hits it. A moveable dtector can be placed on the far wall so that bullets that it it can be collected and counted.

First of all, consider a bullet that can only go through one slit because the other slit has been blocked. It can bounce off the walls of the slit. The diagram shows the setup. The graph at the top shows the normal distribution curve \(P_1\) showing where the bullets will be captured.

Now consider the case where bullets can go through both slits. The normal distribution curve \(P_2\) for bullets that only go through the second slit is the mirror image of \(P_1\). The normal distribution curve \(P = P_1 + P_2\) for bullets going through either slit is the sum of the other two curves.

Two Slit Water Waves

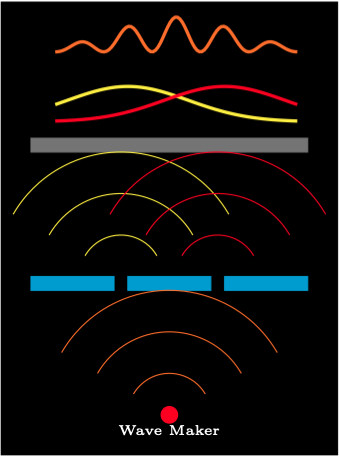

Consider performing the tso-slit experiment in a shallow pool of water. The gun is replaced by a motor driven piston that generated circular water waves. When a water wave passes through a slit it creates new waves radiating from the slit.

When a water wave passes through a single slit it produces a similar normal distribution patterns to bullets. When a water wave passes through two slits the resultant waves are out of phase. The waves after the slits interfere with each other.

The amplitude of a wave from slit 1 at the detector is \(P_1 = |\psi_1|^2\), \(\psi_1 = h_1e^{i(\omega t + \delta/2)}\) and the amplitude of a wave from slit 2 at the detector is \(P_2 = |\psi_2|^2\), \(\psi_2 = h_2e^{i(\omega t - \delta/2)}\). Where \(h_1,\;h_2\) are the wave amplitudes, \(\omega\) is the wave frequency and \(\delta\) is the phase difference that is related to the distance between the slits. The combined amplitude is not the simple sum, but the sum of moduli.

When \(h_1 = h_2 = h\).

Two Slit Electrons

The two-slit eperiment has been performed many times with electrons with results that can’t be explained by classical physics.

Electrons are produced using an electron gun. This is a box with a hole in it containing a heated metal wire that is negatively charged. An electron detector, similar to a geiger counter, detects electrons by generating a click sound when an electron hits it.

Electrons are indivisible subatomic particles, so each electron generates a distinct click at the detector. The clicks occur erratically, but average out to similar numbers over longer time intervals. If the wire is cooled to reduce the number of emitted electrons and a second detector is added, then only one detector will click for each electron, never both.

We can conclude that each electron hits only one detector and always in its entirity. They are behaving like particles.

When measuring the probability, electron detector records a wave like interference pattern! So, the experiment concludes that electrons sometimes behave like particles and sometimes behave like waves.

The method of combining the probabilities for waves also works for electrons, except that the probability amplitudes must be complex numbers!

Also, from this experiment there is no way of knowing which slit each electron passes through.

Observing Electrons

If a light source is added to the experiment between the two slits at the other side to the electron gun, then each electron will emit a flash of light when it passes the light source. This enable the determination of which slit each electron passes through.

When the experiment is performs each electron will create a click from the detector and a flash from one side of the light source, never both. This determines that each electron can only pass through one of the slits. The probability measurements now record a particle like pattern with no interfernece!

If the intensity of the light is reduced then we always see the flashes of the smae brightness. If we reduce the brightness further then some electreons will register a click but not a flash as they escape detection. We now have three categories of electrons, those that went through slit 1, those that went through slit 2, and those that weren’t detected. If we plot the probabilities, those electrons that were detected going through a slit behave like particles. Those that escaped detection behave like waves!

So, electrons that were detected by a flash when they passed though a slit will have been hit by a photon from the light source. The momentum of a photon is given the the Planck constant divided by its wavelength \(p = h/\lambda\). The momentum of the photon deflects the electron changing its behaviour.

The photon momentum can be reduced by increasing its wavelength. Unfortunately if the wavelength is longer than the distance between the slits then it is no longer possible to determine which slit the electron passed though. In this case the deflection caused by a photon’s momentum is small enough for the wave like behaviour to return!

Experiment Conclusion

In an experiment for electrons there is a complex number called the probabilty amplitude \(\phi\). The probability of each event in the experiment is \(P\). Where \(P = |\phi|^2\).

-

If there is more than one option where the path of two events path is not known then interference is observed \(\phi = \phi_1 + \phi_2\), \(P = |\phi_1 + \phi_2|^2\).

-

If the paths of two events are known then the interference is lost \(P = P_1 + P_2\).

It is now considered impossible to know exactly what causes these results. It would require a fundamentally new theory to change this which may not exist!

Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle

Werner Heisenberg concluded from these experiments "It is impossible to design an experiment to determine which slit the electron passes through, that will not at the same time disturb the electrons enough to destroy the interference pattern".

The uncertainty principle relates the uncertainty of a particle’s position \(\Delta x\), the uncertainty in the particles momentum \(\Delta p\) and the reduced Planck constant \(\hbar = h/2\pi\).

Probability Wave Amplitudes

Experiments have shown that sub-atomic particles sometimes behave like particles and sometimes behave like waves. In fact they are neither!

Quantum theory provides a new way of representing thinks by defining an amplitude to every event that can occur. If an event involves the reception of a particle then an amplitude can be given for finding the particle at any given place and time. The probability of finding the particle is proportional to the square of the absolute value of the amplitude.

It is important to note that the amplitude is a complex number. This may seem strange, but complex numbers each have two distinct values and the mathematics of complex numbers is far more elegant than the mathematics of real numbers.

Given that an amplitude \(\phi\) varies sinusoidally. A location can be defined by a position vector \(\vec{r}\). The frequency of the amplitude is \(\omega\). The wave number is a vector quantity \(\vec{k}\) is the spatial frequency of a wave. It is the number of wave cycles divided by the length.

This corresponds to a particle of known energy.

Its momentum is also known and related to the wave number.

This limits the idea of a particle as the probability of finding a particle is given by \(|\phi|^2 = 1\). The probabilty of finding the particle is the same everywhere. We know its momentum but can’t determine where it is!

There is also an issue with short length wave packets. They are actually a combination of different wavelengths.

It does have a fixed length. It does not have a unique wavelength! This means that it doesn’t have a definitive momentum!

Size of a Hydrogen Atom

Early models of Hydrogen being a nucleus with an electron orbiting it simply can’t work. An orbiting electron would emit light, lose energy and fall into the nucleus. That obviously doesn’t happen. It can’t be correct by quantum theory as if the electron was at the nucleus both its position and momentum would be known.

Now assume that thee electron is at an average distance \(a\) from the nucleus. Then its momentum must be of the order of \(p = \hbar/a\). Its kinetic energy must be \(E = \frac{1}{2}mv^2 = p^2/2m = \hbar^2/2ma^2\), where \(m\) is the electron mass.

The potential energy of an electron is \(E = -ke^2/a\) where \(k\) is the Coulomb constant and \(e\) is the electron charge.

The total energy can be determined.

The energy is minimal when the derivative is zero.

Multiply by \(a^3\) and reorganise.

This is the Bohr radius, the approximate distance between and electron and the nucleus of a Hydrogen atom.

Substitute Equation (9) into [ha] and divide by \(e\) for convert Joules to eV.

The energy is negative which means that it requires this amount of energy to ionize Hydrogen. It is called the Rydberg constant.

This explains why we don’t fall through the floor. Trying to force atoms close together requires a higher energy state which is resisted. This is a purely quantum effect which is totally opposite to classical theory!