Astrophysics

Kepler’s Laws

Johannes Kepler studied positional data for the planet Mars and came up with three Laws between 1609 and 1619 which describe how a body orbits around another. All of Kepler’s calculation were done using geometry as it was the only mathematical tool available then.

In the late 17th century calculus was discovered independenly by Sir Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibnitz. There was much controversy over which man discovered it first with Newton accusing Leibnitz of plagiarising his work. Calculus became a very powerful tool which enabled Newton to derive Kepler’s laws from first principles.

Kepler’s First Law

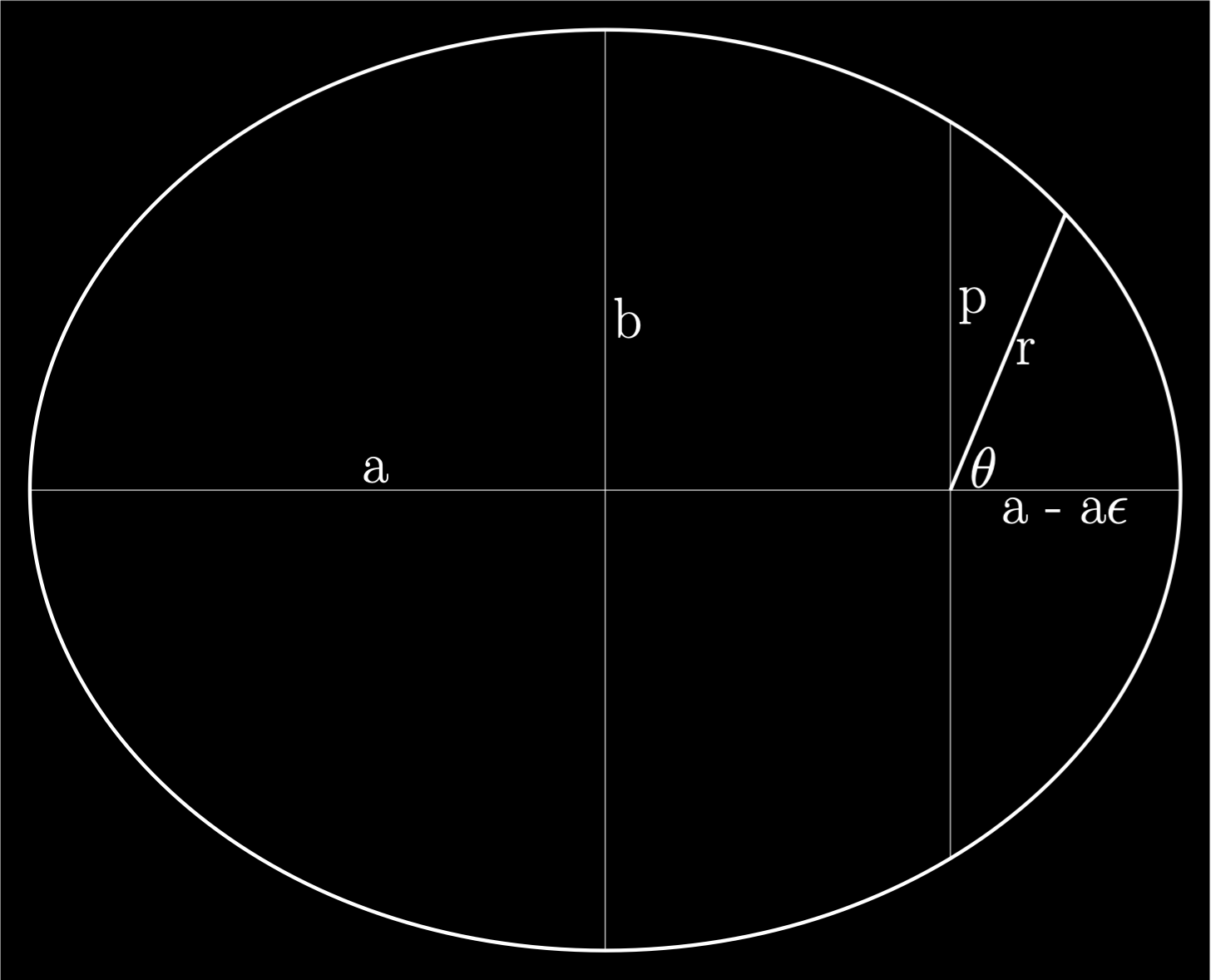

The orbit of every planet is an ellipse with the Sun at one of the two foci.

The variables are:

-

\(a\) is the semi major axis distance.

-

\(b\) is the semi minor axis distance.

-

\(e\) is the eccentricity of the ellipse.

-

\(p\) is the semi latus rectum distance which passes through a focus.

-

\(\theta\) is the real anomaly which is the angle the planet has orbited from perihelion.

-

\(r\) is the distance from the planet to the sun.

The values \(a\), \(b\) and \(e\) are related by the equation:

The area of the ellipse \(A = \pi ab\).

The cartesian equation of an ellipse centred on its focus is:

Put Equation (2) in polar coordinates \(x = r\cos\theta\), \(y = r\sin\theta\).

Substitute Equation (1) into Equation (3).

Expand the square, multiply by the common denominator and reorganise.

Collect \(r\) powers.

This is a quadratic equation in \(r\), calculate the discriminant.

Solve Equation (6) for \(r\).

Take the positive square root.

At the semi latus rectum \(x = 0\) and \(y = p\). Substituting these values and multiplying by \(b^2\) gives:

This gives the equation of the ellipse to be:

Newton’s Derivation of Kepler’s First Law

Kepler’s first law can be derived from Newton’s Laws. The derivation is not very straightforward.

Newton stated that the energy of a body orbiting another is the difference of the kinetic energy and the gravitational potential energy. This is a constant due to the conservation of energy:

Where \(G\) is the gravitational constant, \(m\) is the mass of the orbiting body and \(M\) is the mass of the body being orbited.

Note that for an elliptical orbit \(E < 0\). This is because the gravitational potential energy is greater than the kinetic energy. This might seem strange, but Newton’s Laws are known to be very accurate!

The angular momentum \(L\), which is also constant due to the conservation of angular momentum, is given by:

Substitute the value of \(\dot{\theta}\) from Equation (13) into Equation (12).

Multiply by \(2/m\) and reorganise.

Take out a factor.

Define a constant p. This will be the the semi-latus rectum distance.

Substitute Equation (17) into Equation (16).

Complete the square from the last two terms.

Extract a factor of \(1/p^2\) from the first two terms.

Substitute Equation (17) for a single p in the second term.

Define a constant e. This will be the eccentricity.

Substitute.

Replace r with \(1/\rho\) and take the square root.

Rearrange Equation (13) replacing r with \(\rho = 1/r\).

Now.

Rearrange.

Compute.

Substitute Equation (25) and Equation (27).

Substitute Equation (24).

Write as integrals.

Define.

Substitute into Equation (31).

Integrating gives \(\theta = \alpha\).

Rearranging gives the equation of an ellipse.

Kepler’s Second Law

A line joining a planet and the Sun sweeps out equal areas during equal intervals of time.

Kepler determined how to describe the true anomaly in terms of time. This is not a straightforward process.

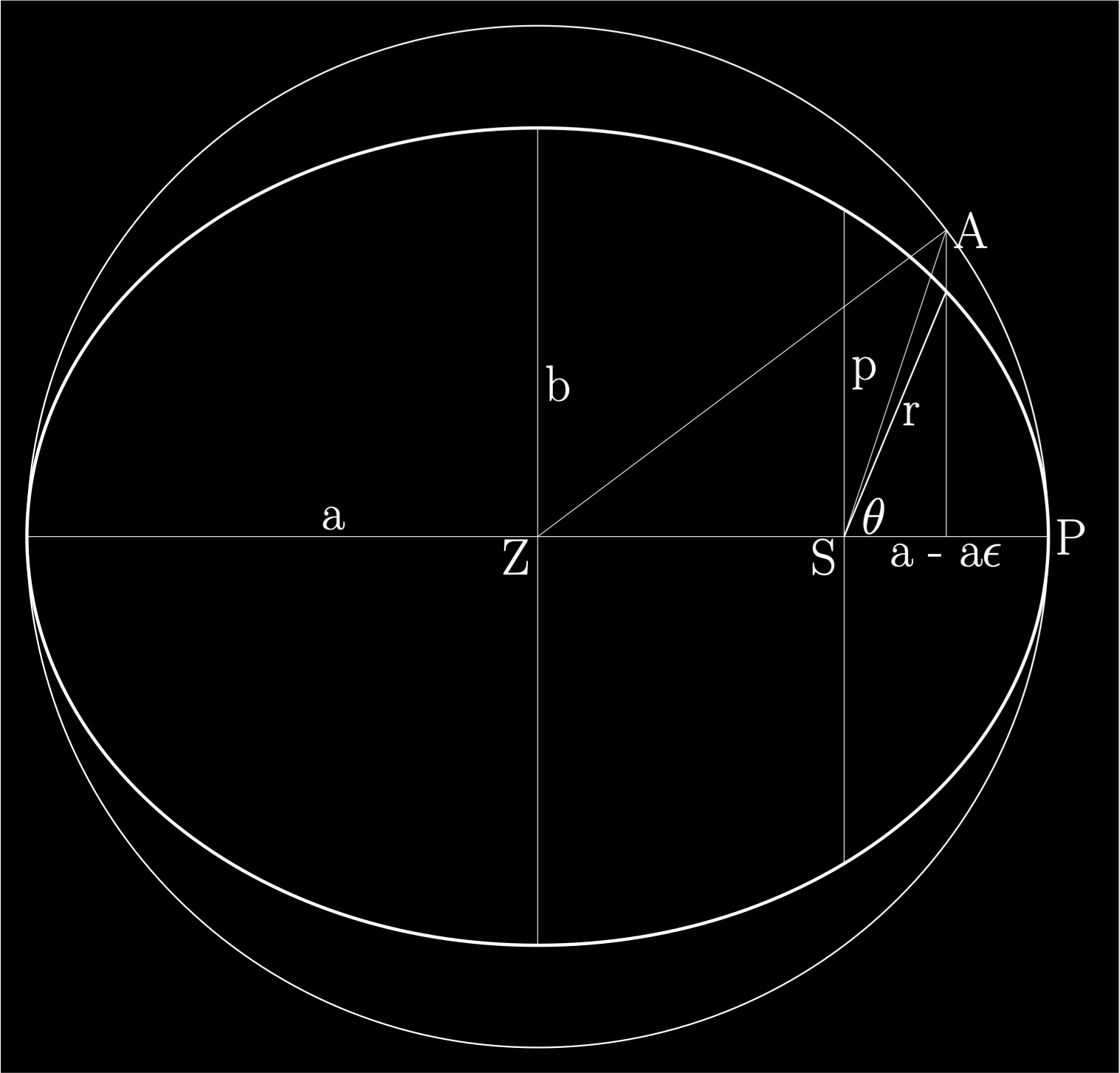

Mean Anomaly

The mean anomaly \(M\) sweeps out the same area of the containing circle for equal intervals of time. The mean anomaly can be expressed as a function of time \(t\) given the orbital period \(P\) by:

The area swept out is:

Eccentric Anomaly

Kepler defined an intermediate angle called the eccentric anomaly \(E\) to the point A on the diagram. It is chosen such that the area of the section \(\widehat{PSA}\) on the diagram is the same area as the area swept out by the mean anomaly. The area of \(\widehat{PSA}\) is the area of the sector \(\widehat{PZA}\) minus the area of the triangle \(\widehat{ASZ}\). Multiplying by two and dividing by \(a^2\) gives Kepler’s equation:

Kepler’s equation cannot be solved analytically. As the eccentricity is small for most planets, it can be approximated using a power series expansion. It can also be solved numerically using iteration.

True Anomaly

The final step is to be able to derive the value of the true anomaly \(\theta\) from the eccentric anomaly \(E\). From the diagram we can see that:

The radius \(r\) can be calculated from the eccentric anomaly by combining the ellipse equation with the true anomaly equation.

Newton’s Derivation of Kepler’s Second Law

The angular momentum \(L\) of an orbiting particle is:

Where \(I = r^2m\) is the moment of inertia of a particle of mass \(m\). The angular momentum is constant as there is no torque.

The area swept out \(A\) is given by:

Combining the equations gives:

So, the rate of change of area with respect to time is constant.

Kepler’s Third Law

The square of the orbital period \(T\) is directly proportional to the cube of the semi-major axis \(a\) of its orbit.

Kepler’s equation for the third law is:

Newton’s form of Kepler’s Third Law is:

Where \(M\) and \(m\) are the masses of the two bodies. In the case of our solar system the mass of the Sun is considerably greater than the masses of the planets. In general if \(M >> m\), then the \(m\) term can be ignored. For our solar system if \(T\) is measured in years and \(a\) is measured in AU then for any body orbiting the Sun: